Recently I was invited to give a 1-hour tutorial at the Computing in Topological Structures workshop (CTS 2022) held partially by zoom and in person in Sochi, Russia. Here are the slides plus some commentary. The whole talk turned into a very long post, so I chopped it in two. This is the first half, largely about playing infinite games (really).

Yes, Russia. Friends and even family objected because of the war but I pointed out that when the US is bombing countries (Vietnam, Serbia, Afghanistan, etc, etc) there’s no movement to boycott US mathematics. I’ve worked with some of these colleagues for many years. It’s not their war. I do not support cultural boycotts.

Добрый день. Я очень рад принять участие в этой конференции. Спасибо за приглашение.

Good afternoon. I am very happy to take part in this conference. Thank you for the invitation.

This is Vancouver BC Canada, where I’m coming from. It’s on the other side of the world from Sochi.

And this is UC Berkeley California, where I arrived as a fresh-faced grad student in 1966 (56 years ago!). (At the time nobody said that because of the Vietnam war I shouldn’t go.)

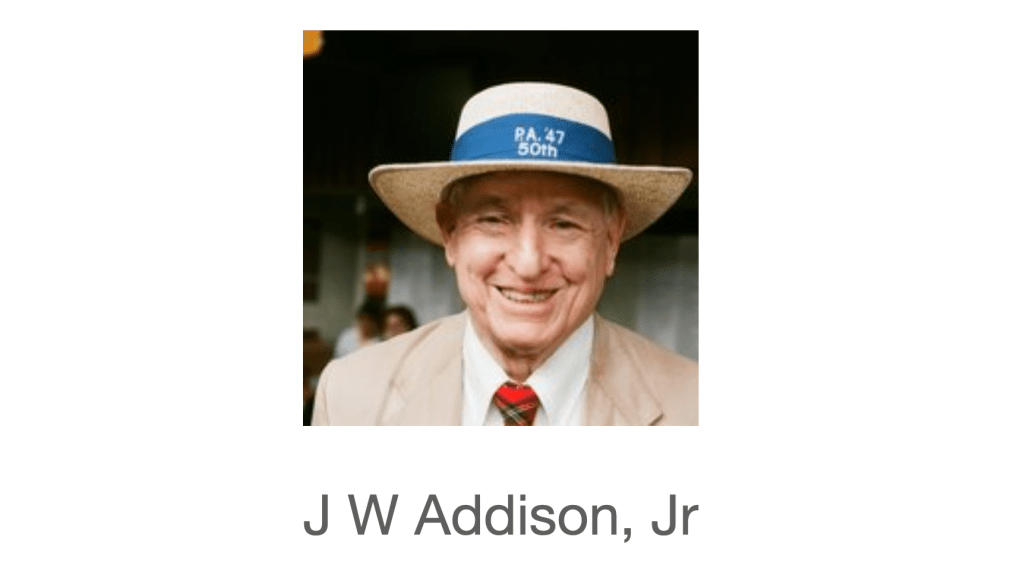

I was having lunch one day with the Canadian contingent and they told me about this great logic course given by a guy named Addison. I took it, my formal introduction to Logic, and it was the best course ever. The next year I took Addison’s seminar on definability and was introduced to the Baire Space

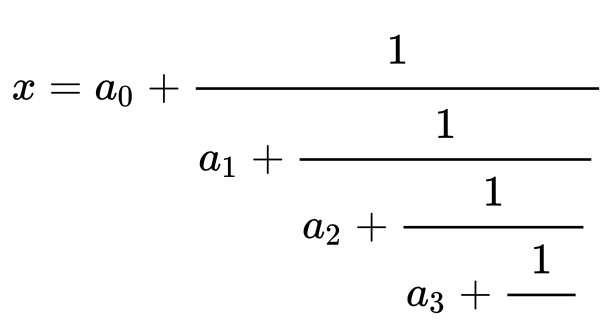

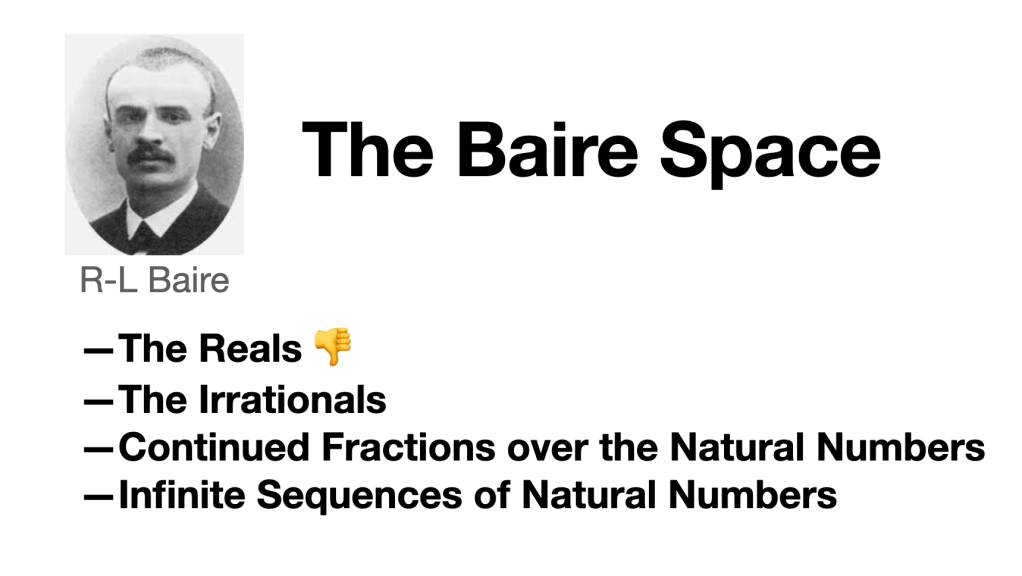

Topologists started studying the reals but discovered they were very inconvenient – for example the product of the reals with itself is not isomorphic to the reals. If you take only the irrationals, these problems disappear. Every irrational has a unique continued fraction expansion and vice versa. Eventually they dropped the fractions and worked directly with infinite sequences of natural numbers – the modern Baire Space.

(About topology: this talk was given to an audience of topologists, so if your an average reader, you may get lost. Informally, a topological space is a nonempty set with a notion of closeness.)

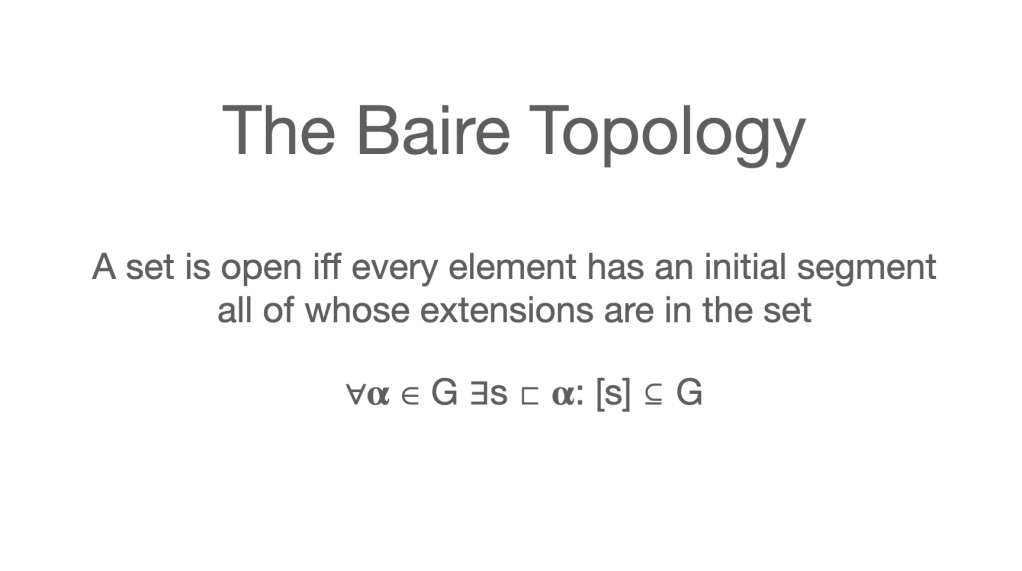

In terms of sequences, the Baire Space has the finite-open topology. Two elements are close if they have a long common initial segment. A set is open if all points sufficiently close to an element are also in the set.

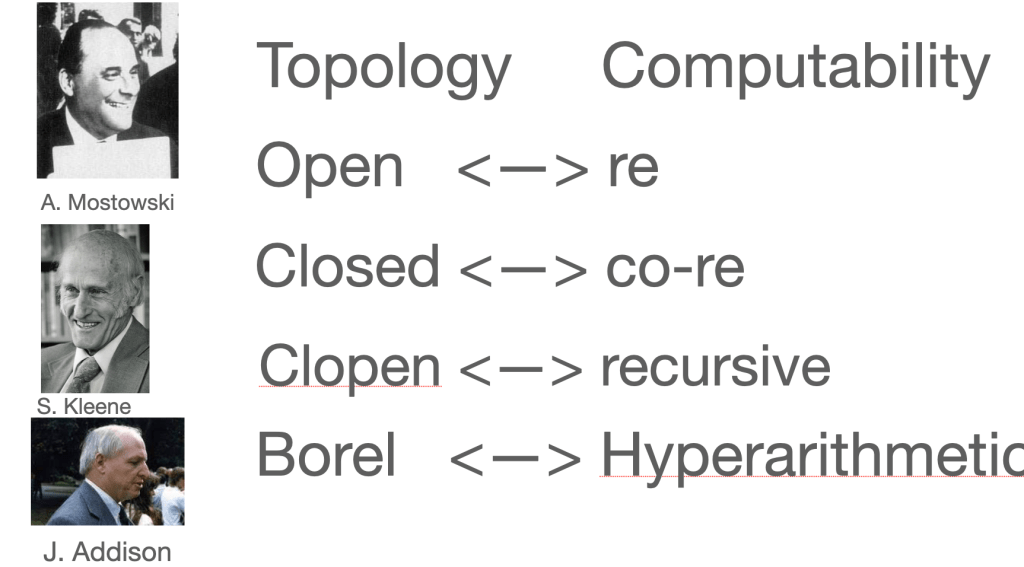

Addison then took up a fascinating topic, an analogy between topology and recursive function theory. A set is re (recursively enumerable) if some continuously operating machine can list (enumerate) its members. How can you enumerate can uncountably infinite set?

This is the definition that can be analogized. An element of the Baire Space can be written on the infinite tape. If the machine eventually accepts it, can have examined only a finite number of components, hence the set is open. To make this work in the other direction we need infinitely many states ,of the machine. Thus, in this analogy open sets correspond to re.

Mostowski was the first to look for an analogy but he got it wrong – he thought analytic was like re. Kleene corrected him and Addison at least popularized the re <-> open analogy.

Addison assigned me the (ambitious) task of doing better than Lyudmilla Keldysh, the Russian mathematician (Addison spent a year in Poland in 1957 and was very familiar with Eastern European mathematics. He didn’t let the Cold War stop him.)

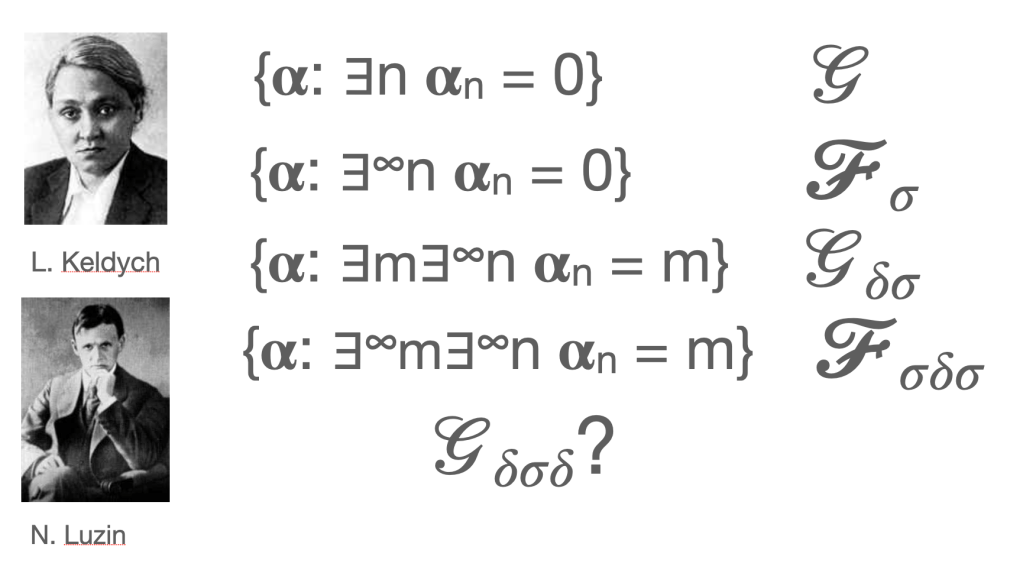

Keldysh had set herself the task if finding simple sets that witnessed the fact that Borel hierarchy was not degenerate. She came up with these four sets. The first is open and it is easy to see it’s not closed – <1,1,1,..> is a limit point of the set but not in the set. Showing that the fourth one (all sequences where infinitely many numbers appear infinitely often) is no simpler using techniques of that time is exceedingly difficult. Luzin included the proofs in his book

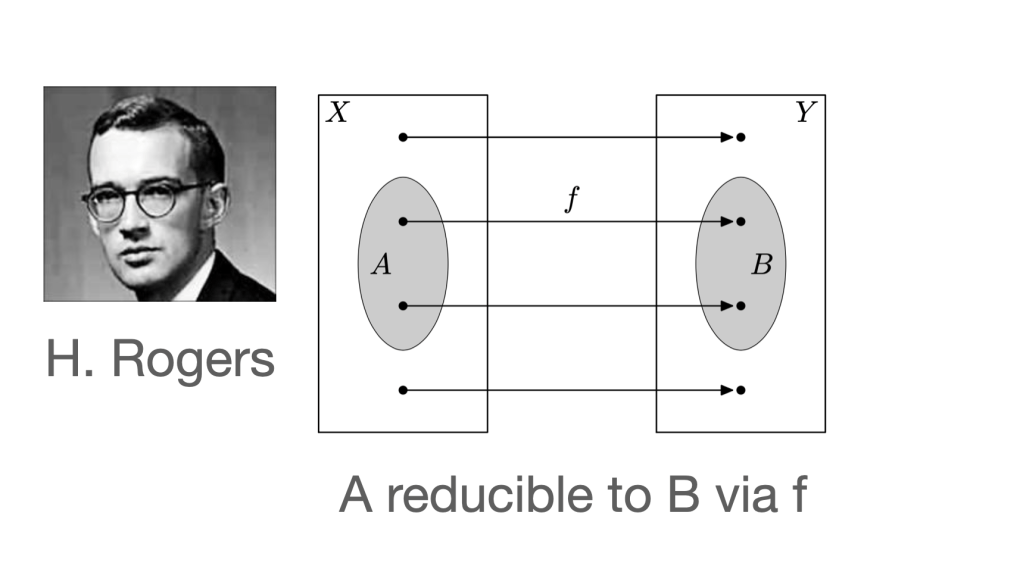

Addison passed on a paper in which Hartley Rogers solved an analogous problem using reducibility by recursive function.

No prizes for guessing this.

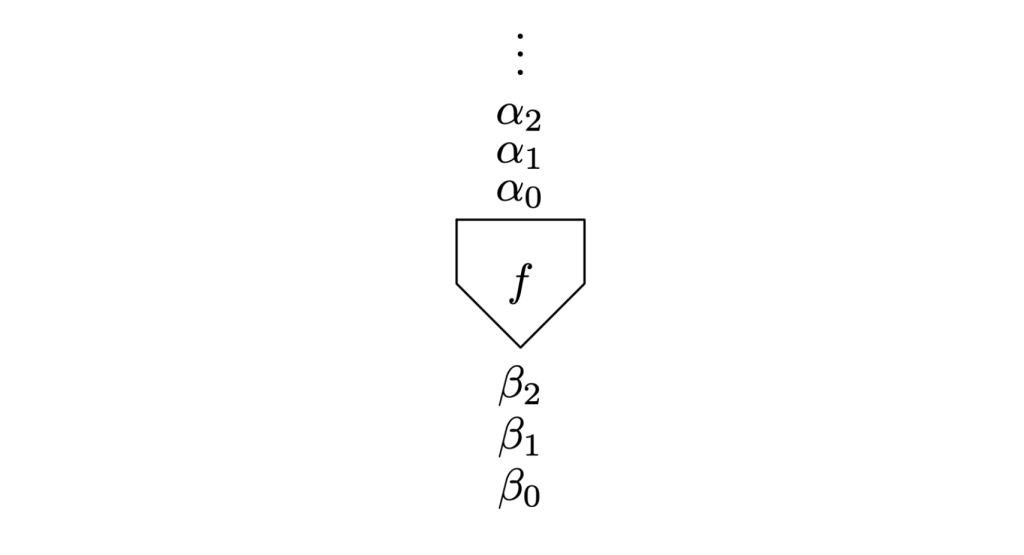

The finite-open topology implies that a function is continuous iff aTuring machine computes it incrementally – reading some of the input off a tape, printing some output, reading more input, printing more output, etc. If we allow a countably infinite number of machine states, any continuous function can be computed this way.

In modern terminology, this means that f is continuous iff it can be computed by a filter, a continuously operating device which consumes an input stream one data item at a time and produces an output stream once data item at a time. For complete generality we must allow the device to have countably many states, and not insist that input and output rates be the same.

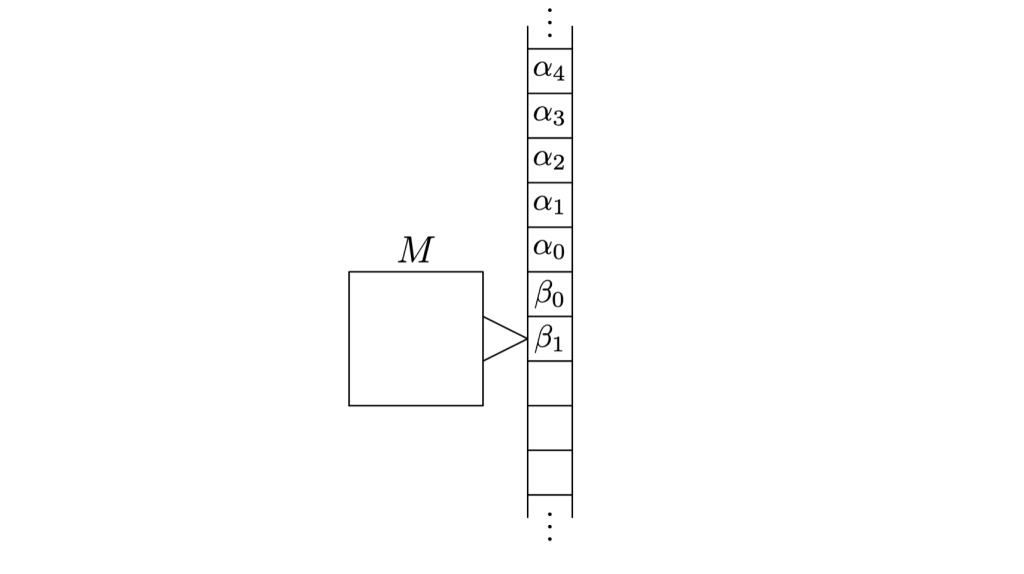

I had one huge advantage over Keldych, I learned about infinite games (from Addison, of course). Every subset of the Baire Space determines such a game. Players one and two alternate play natural numbers indefinitely and construct an element of the Baire Space.

Player I wins iff the resulting set is in S, and player II wins if it is not.

This can be formalized using the notion of strategy. A strategy for I is a scheme which incrementally produces alphas from betas, and a strategy for II produces betas from alphas. These are clearly continuous functions … hmm.

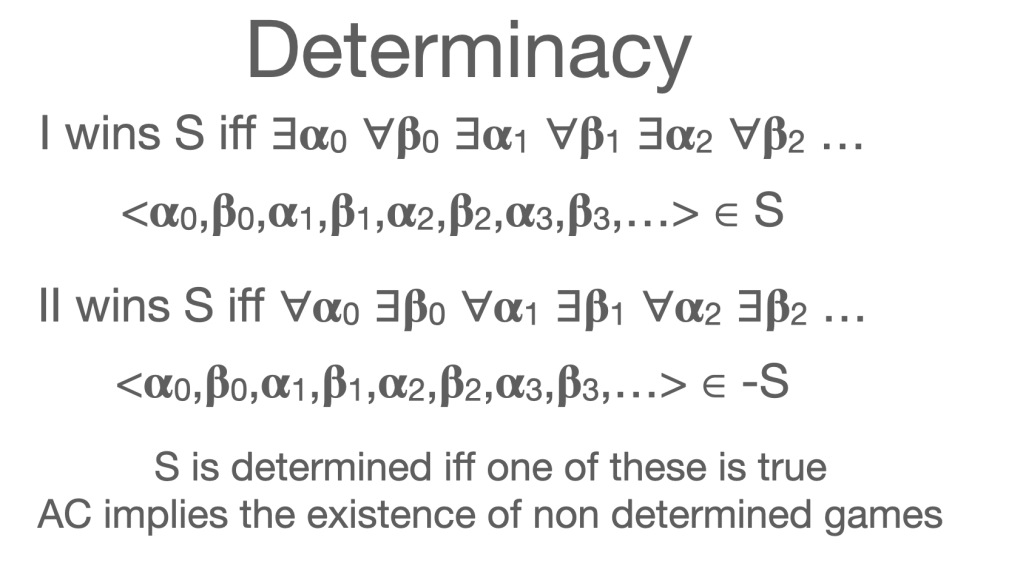

Since there are no ties in the game, you’d expect that one of the players has a winning strategy. After all, the formulas given above are the result of applying the quantifier negation rules. But these are infinite sequences of alternating quantifiers and the finite rules don’t always work.

A game is said to be determined iff one of the players has a winning strategy. Unfortunately the Axiom of Choice (AC) implies the existence of non determined games.

How complex must these non determined games be? Gale proved that open games are determined and eventually this was extended (with difficulty) to the first four levels of the Borel hierarchy.

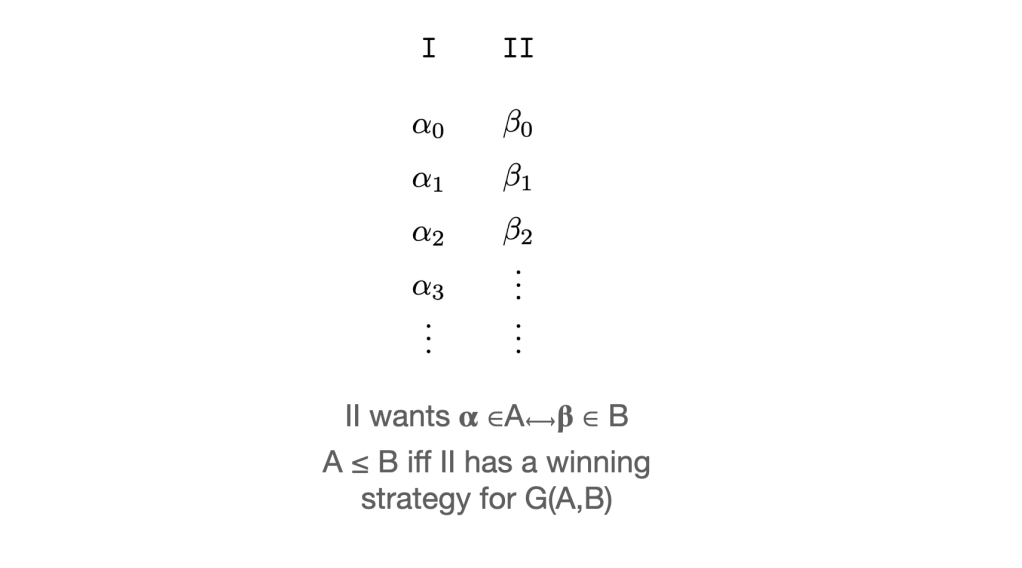

All this suggested a game in which every strategy is a continuous function and every continuous function is a strategy. Given two subsets A and B of the Baire Space, G(A,B) is a two player game in which on each move I plays a natural number and II plays a natural number or passes – but not forever. II is trying to imitate I and wins if his sequence bears the same relationship to B as I’s sequence does to A. This game characterizes ≤.

In short, every strategy for II is a continuous function and every continuous function is a strategy for II. And every winning strategy for II is a continuous function that reduces A to B, and vice versa.

With this game I was able to easily prove that Keldysh’ examples were complete for their levels and hence not simpler.

Tony Martin, a real heavy weight, proved that all Borel sets are determined – a brilliant proof. This simplified my task of describing the Borel degrees (which he showed were, modulo negation, well ordered).

To characterize the Borel degrees I needed some heavy-duty technology. The first was Kantorovich’s omega boolean operators.

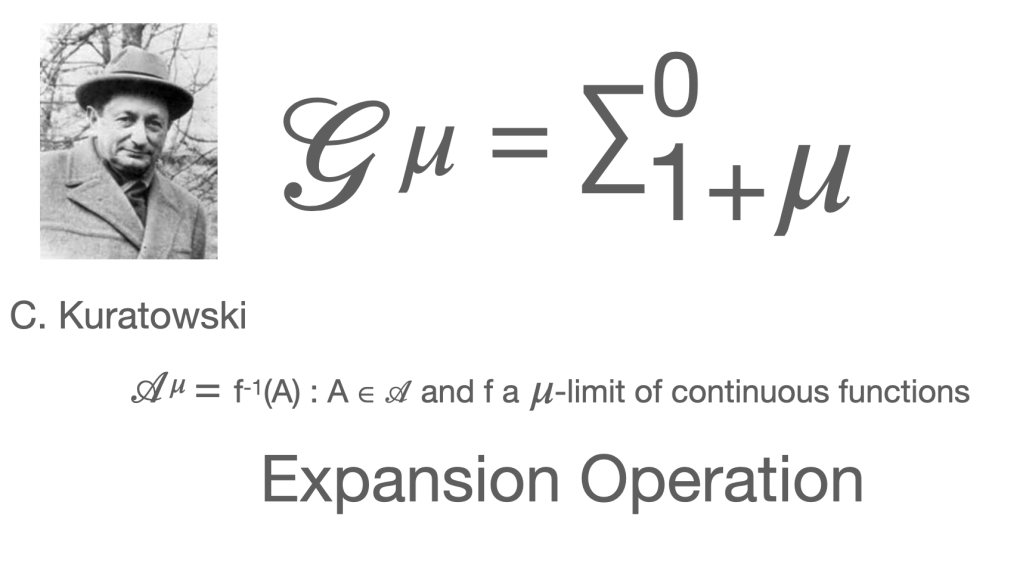

The second was the expansion operation, implicit in Kuratowski.

Then I had to proves this harmless looking identity which is seriously nontrivial. I borrowed techniques from Kuratowski.

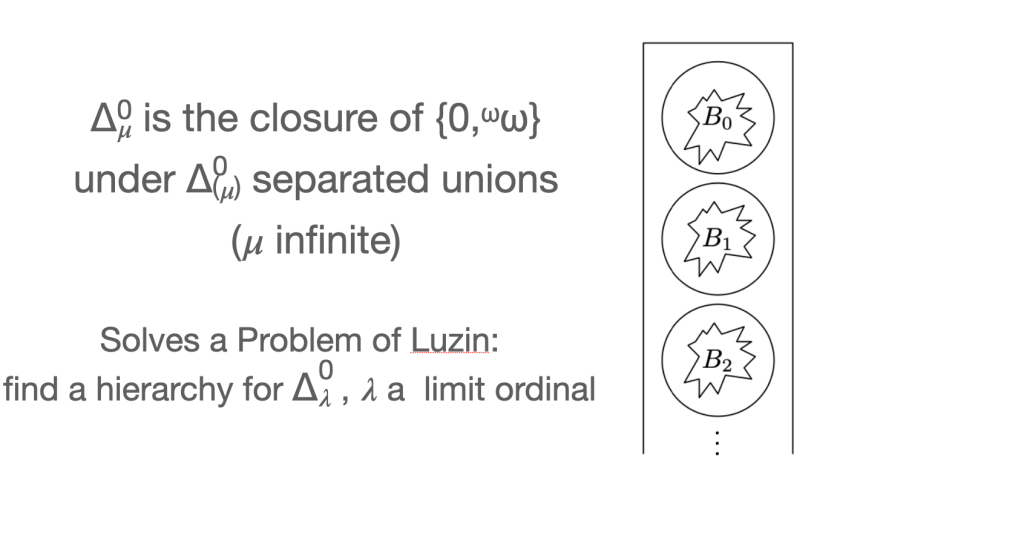

Then I had to solve a problem of Luzin. Luzin was probably stumped because he didn’t know about separated unions (they’re not in his book). Oddly, my proof was purely classical (borrowing ideas from Kuratowski again) and didn’t use games.

I used games to define arithmetic operations on degrees. These included successor, addition and multiplication by countable ordinal.

/

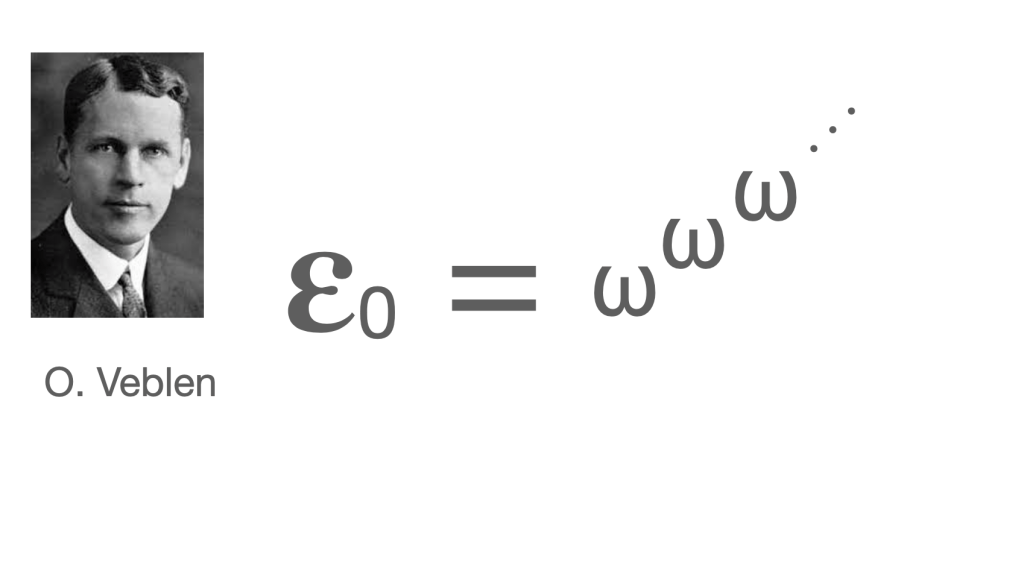

Now I could calculate the order type of the Borel degrees. This used another piece of technology, Oswald Veblen’s calculus of ordinals. We begin with epsilon-0, the first fixed point of exponentiation.

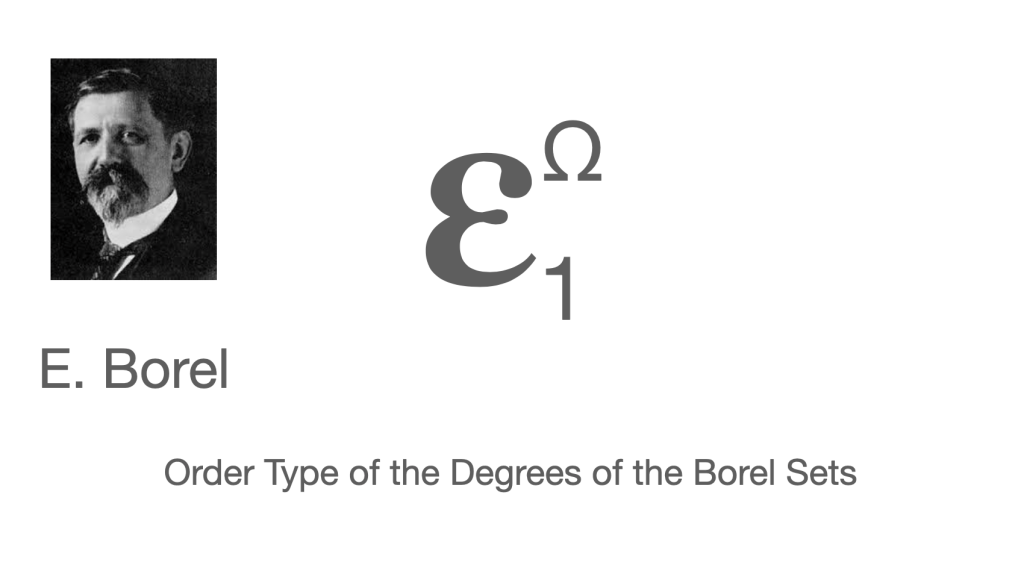

Then we start taking fixed points of our series … epsilon-1 is the fixed points of the epsilon series, epsilon-2 the fixed point of epsilon-1,… and so on.

We do this Ω times (Ω the first uncountable ordinal) and we finally skip the countable ordinals. We reach Ω and the next fixed point after that is the order type of the degrees of the Borel sets.

which properties of the program can be derived logically.

This is the end of Part I, the hard one. The second half is about programming, so you should have better luck.