I am a computer scientist (emeritus professor at the University of Victoria, Canada) with a part-time interest in rhetoric. I’m going to give you a quick tutorial in using a formula devised by Marcus Tullius Cicero. It will make articles you write to persuade people (like persuading granting authorities to fund you) more effective and memorable.

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion but few techies have been trained in it. Presumably our bosses think that being, say, a software engineer doesn’t, as part of our job description, involve persuading anyone of anything. “Shut up and code” seems to be the message.

Nevertheless this simply isn’t true. Depending on where you are in the chain of command, you may have to persuade your colleagues to adopt an architecture you propose, take on a project you’re backing, or accept that your software works.You may have to make a case for being promoted, or being awarded a grant.

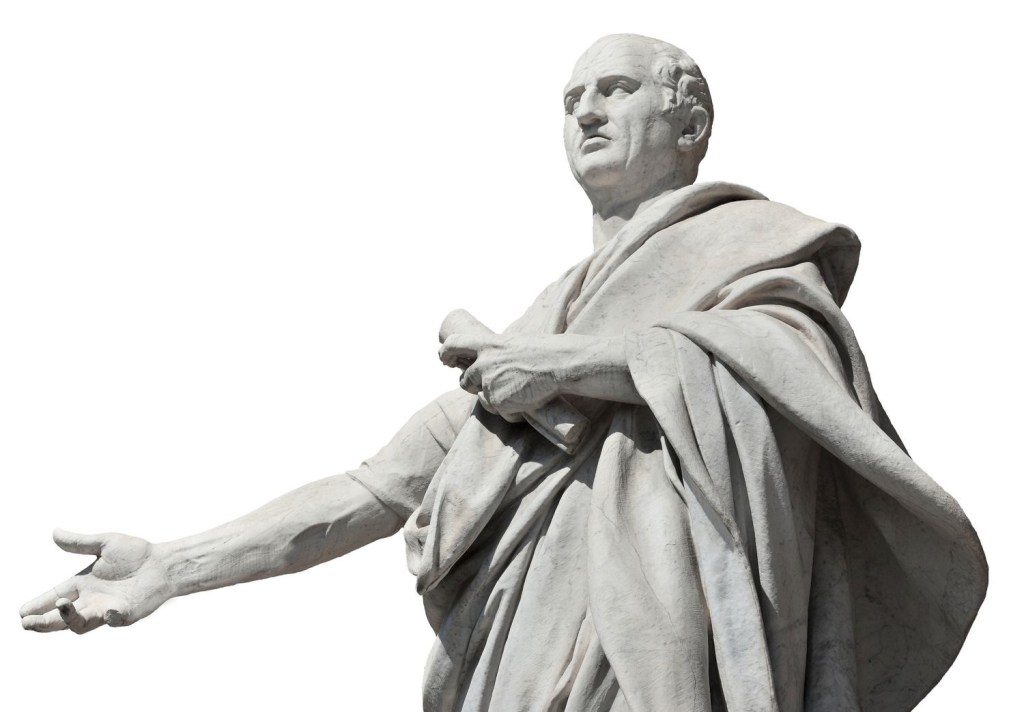

Cicero’s formula

None of these tasks are easy but some simple rhetorical principles can make a big difference. Cicero, the famous Roman politician and rhetorician came up with an easy formula that is widely applicable.

Cicero’s model oration has five parts: the exordium, or introduction; the narratio, or background; the confirmatio, or supporting case; the refutatio, or anticipated objections, and the peroratio, or summing up.

The exordium

The exordium is the introduction, where the speaker introduces themself and lays out exactly what proposition they hope to persuade the audience of. The speaker should give some information about their background and qualifications.

The narratio

The narratio is background, it sets the stage for the presentation. It should say how the question arose, and describe different opinions about it. It should say why the question is important and what the consequences of resolving it will be.

The confirmatio

This is where the speaker (or writer) puts forward the case in support of the proposition. This is the most important part of the speech and will typically be divided into several sections.

The refutatio

Here the speaker anticipates objections and refutes them. For example, one might object that no one has tried this before and the refutation is, there’s always a first time.

The peroratio

This is the final part or summing up. The speaker may chose to simply summarize what they’ve already said – the peroration is not the place to bring up new topics.

Your grant application

Now let’s apply this model to a grant application. You want to persuade the authorities to give you a hopefully bigger grant to follow up on your research so far or possibly strike out in a different direction.

I have some expertise here because I spent two years on the Canadian computer science grant selection committee. Our biggest problem was keeping track of who was proposing what. The proposals were typically badly organized, with important information hard to find. If the candidates had used Cicero’s model, our jobs would have been a lot easier

A good exordium

The biggest mistake with the exordium is simply to omit it! Instead, they jump right into the narratio … e.g. ‘In recent years much study has been devoted to … ‘. Sometimes the narratio goes on for several paragraphs.

I strongly recommend a short but sharp exordium where you tell the reader what problem you’re attacking and exactly what you are proposing e.g. ‘we present a solution to the error problem using Fourier coefficients …’

Instead, most candidates offered a long rambling narratio with the exordium buried in the middle. Sometimes we had serious difficulty figuring out exactly what they were proposing – what was their basic idea.

This mistake – burying the exordium – is so common it’s become standard. You can see it also in the abstracts of colloquia. Grad students imitate it, thinking that’s how you’re supposed to write abstracts.

Yes, almost everybody does it, but if you use a proper outline, your proposal will stand out as easy to read and remember.

The narratio

This should be the easiest to write since long narratios are so common, but ‘long’ becomes the problem, The danger is that the narratio consumes the article, which becomes a tutorial. Part of the problem could be that authors lack confidence in their own ideas and play them down in favour of describing the proposals of ‘experts’.

If you don’t have confidence in your own proposal you’re unlikely to convince anyone else that it’s worthwhile. So be bold and back up your idea.

The narratio should make clear that the problem you’re attacking is hard and (probably) others have tried and failed.

The confirmatio

Here is where you make your case. As a general rule, successful applicants have a good or at least plausible idea, and a strong track record.

If you have a strong record it’s tempting to summarize it immediately in the confirmatio but I don’t think that’s a good idea. No matter your record you should begin with explaining your idea and why you think you can make it work. If you’ve already made some progress, excellent.

Now the track record? Hold on. The next part of the confirmation should describe how you’re ready to work on your idea e..g. thee team you’ve assembled, such as grad students and post docs. Also ongoing collaborations.

Finally it’s time for the track record. Don’t be shy.

The refutatio

Now the refutatio, where you anticipate objections. Here you can list problems that are bound to arise, and the ideas you have for getting around them.

There are some generic objections that you might want to take into account.

One is that the problem you’re solving is of no interest. Another is that the solution you’re proposing is impractical. Or that it’s already been tried, or that the problem has already been solved and your solution is therefore of no interest.

Your responses will vary; you may say, for example, that your solution has special merits not possessed by existing solutions. It’s probably best to answer plausible generic objections before getting into special problems.

The peroratio

Here the best strategy is to summarize, in a paragraph, the whole proposal – who you are, what your idea is, why it’s good, why you’re in a good position to carry it out, why it’s of interest. A concise summary will be invaluable to the people assessing your proposal.

And there you have Cicero’s recipe. The alert reader will have noticed that this article itself follows the recipe.

The first paragraph is the exordium. The narratio continues until the section “Your grant application. The confirmatio carries through till the heading “The refutatio” where it anticipates problems and discusses how to deal with them – in other words, it’s the main article’s refutatio. Finally, the last section, after the heading “The peroratio” is a summary and as such the main article’s peroratio.